Review by David Otte/photos by the author

Review by David Otte/photos by the author

Between the current state of the economy and the fact that the population of dedicated model railroaders appears to be slowly shrinking, any new hobby manufacturer attempting to enter this marketplace will quickly recognize the gamble involved. As such, its initial major product release will be, for all intents and purposes, the company’s defining moment. Complicating matters further, the model railroading community of late has become a tough crowd to please with their expectations set pretty high for both quality and prototypical accuracy while also demanding that affordability be maintained. It’s quite a juggling act, but one that newcomer ScaleTrains has endeavored to pursue.

Built around a small group of folks who are both model railroaders and experienced industry insiders, ScaleTrains’ approach to the market is threefold. Referred to by the company as Operator, Rivet Counter, and Museum Quality, each brand offers a different level of detail and operational parameters to meet any modeler’s budget. Both locomotives and rolling stock in HO and N scale are being offered, along with a contingent of Kit Classics that allow the craftsman in us all to enjoy the construction of some old-fashioned plastic freight car kits.

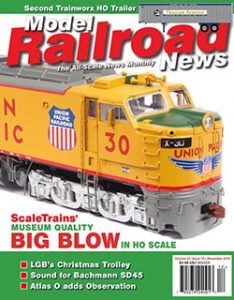

Over the past year, ScaleTrains has released a boxcar kit, intermodal containers, Union Pacific (UP) excursion service water and fuel tenders, and ready-to-roll tank cars in these various lines, but the company’s first locomotive release — its defining product offering — has just arrived on the scene and it’s a doozy: Union Pacific’s 8,500-hp Super Turbine. A signature locomotive of Uncle Pete’s diesel era fleet, this HO-scale behemoth marks the first time a ready-to-run plastic model of the three-unit prototype has been massed produced in 1:87. Offered under both the Rivet Counter and Museum Quality brands, the Super Turbine presents a new level of sights and sounds yet to be experienced by the average HO-scale modeler — prepare to be wowed!

Uncle Pete’s Adventures with Big Blow

Uncle Pete’s Adventures with Big Blow

Since the gas turbine electric locomotive (GTEL) is not your run-of-the-mill motive power, a quick overview of its development by UP and partner General Electric (GE) is certainly worth discussing.

To say the least, UP ran through some pretty wide-open spaces out West. Big country and steep grades required some hefty horsepower to pull UP’s heavy tonnage trains at the fastest speeds possible. These environmental demands on the railroad had UP’s motive power department in a continual search for the biggest and best locomotives. Out of this development came the now famous Challengers, Big Boys, and, of course, the GTELs.

It was General Electric Company’s early experimentation with turbine designs, first powered by steam and later gas, that introduced UP to this radical new type of motive power. While the steam turbine was branded a failure back in 1939, GE was inspired by the accomplishments of the Brown-Boveri Company and that company’s introduction of a 2,200-hp gas turbine electric locomotive constructed for the Swiss Federal Railroad in 1941. Subsequently, GE teamed up with Alco to design its gas turbine electric, which they unveiled in the fall of 1948. The streamlined locomotive, rated at an incredible 4,500-hp, had cabs at either end of the carbody, featured eight drive axles in a B-BB- B arranged running gear, and utilized a low-cost fuel generally known as “Bunker C” fuel oil. Due to the heavy viscosity of this cheap fuel, the gas turbine was also equipped with a steam generator to heat the oil so that it could flow properly.

After surviving eight months of company evaluations, the Alco-GE gas turbine was sent out West to the UP for more extensive testing. Wearing UP colors, gas turbine No. 50 saw systemwide use and performed very well on the most arduous of runs on the Wyoming Division — between Cheyenne, Wyo., and Ogden, Utah, up Sherman Hill, and through the Wasatch Mountain range. After 21 months of notable service and an odometer reading of 101,231 miles, UP 50 was returned triumphantly to GE in the spring of 1951.

At this point, you may be asking yourself, “Just what is a gas turbine anyway?” Perhaps the most familiar form of a turbine today is a jet aircraft engine. The principle is as follows: air is drawn in from the atmosphere and compressed. The compressed air is then super-heated by directly burning fuel in it, and the resulting hot compressed air is used to perform work as it re-expands to atmospheric pressure. In particular, the gas turbine on board the GE locomotives compressed the atmospheric air to six times normal pressure. After the compressed air was further heated, the resulting hot gas moved at great velocity against the curved blades of the turbine, causing a drive shaft to spin. Through gear reduction, the shaft drove four direct-current electric generators, which then supplied power to the eight traction motors. Railroaders later gifted the GTELs with the name “Big Blow” due to the jet exhaust sound emitted from the turbines.

At this point, you may be asking yourself, “Just what is a gas turbine anyway?” Perhaps the most familiar form of a turbine today is a jet aircraft engine. The principle is as follows: air is drawn in from the atmosphere and compressed. The compressed air is then super-heated by directly burning fuel in it, and the resulting hot compressed air is used to perform work as it re-expands to atmospheric pressure. In particular, the gas turbine on board the GE locomotives compressed the atmospheric air to six times normal pressure. After the compressed air was further heated, the resulting hot gas moved at great velocity against the curved blades of the turbine, causing a drive shaft to spin. Through gear reduction, the shaft drove four direct-current electric generators, which then supplied power to the eight traction motors. Railroaders later gifted the GTELs with the name “Big Blow” due to the jet exhaust sound emitted from the turbines.

In general, the gas turbine electric is very similar to the diesel-electric with the only major difference in the prime mover. The turbines used, to a degree, the same trucks, traction motors, and controls as their diesel-powered counterparts. In fact, all the UP’s smaller class gas turbines were also equipped with 250-hp diesel engines for powering the auxiliary equipment and hostling the locomotive at speeds under 25 mph, as well as for bringing the turbine up to firing speed.

GE’s experiment with the gas turbine electric finally paid off. Because the UP was so impressed with the number 50, the railroad placed its first order for 10 examples of the 4,500-hp turbines in late 1951 and numbered them 51–60. The first production turbines, delivered in 1952 and 1953, featured many enhancements to the original design most notably the elimination of the second cab and increased fuel economy. Right from the start, the turbines’ performance was impressive on the average hauling 5,000-ton trains up better than 1 percent grades and without any helpers.

Pleased with the continued success of the GE locomotives, UP ordered 15 additional 4,500-hp units numbered 61–75 and incorporated some major design changes, the most noticeable of which were the recessed exterior walkways along each side of the carbody. These catwalks, which allowed easier access to the internal equipment, earned the second class of GTELs the nickname “Verandas.”

In their first full year of service, the 25 gas turbines handled 10 percent of all UP’s freight trains. Furthermore, it was not unheard of to see the 4,500-hp turbines double-headed, not to mention the occasional sight of a Challenger or Big Boy helping out a turbine with an extra-long train during the final days of steam. There is even a rare event recorded whereby a turbine ended up as the power on a streamlined passenger train when its main motive power broke down. Later, when many of the turbines were set up for multiple-unit (MU) control in the late 1950s, it was common to see the gas turbines MUed with GP9s, F-units, SD24s, and SD40s.

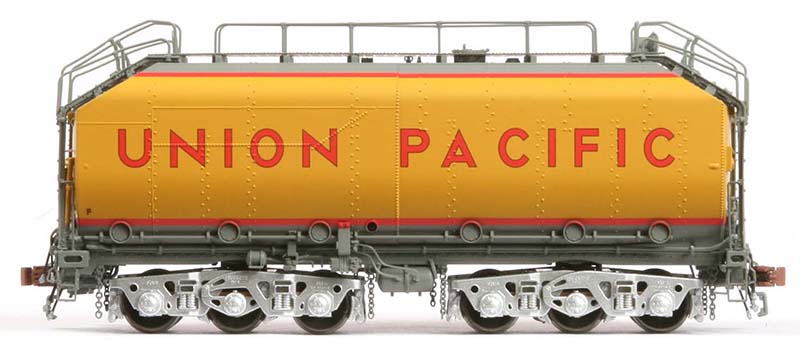

One notable modification to the appearance of the 4,500-hp class was the addition of auxiliary fuel tenders to the fleet in 1956. The running gear was obtained from retired 9000-series steam locomotive tenders with water compartments from two of the tenders spliced together forming a 24,000-gallon fuel tank. This allowed the turbines to operate the 992 miles from Ogden to Council Bluffs, Iowa, without refueling.

One notable modification to the appearance of the 4,500-hp class was the addition of auxiliary fuel tenders to the fleet in 1956. The running gear was obtained from retired 9000-series steam locomotive tenders with water compartments from two of the tenders spliced together forming a 24,000-gallon fuel tank. This allowed the turbines to operate the 992 miles from Ogden to Council Bluffs, Iowa, without refueling.

A final class of 30 8,500-hp “Super Turbines” made their way onto the UP roster between 1958 and 1961. The basis for the new ScaleTrains model, these two-unit locomotives (numbered 1–30) differed from their older brothers in a number of areas. Up front was the control unit, which housed the engineer’s cab controls, air compressors, and an 850-hp Cooper-Bessemer diesel engine, which provided the means for starting up the turbine and for operating the locomotive when the turbine was offline. The trailing turbine unit contained the gas turbine power plant itself and the two 3,500-hp traction generators that powered the 12 traction motors, which drove 12 axles on the new C-C arranged trucks employed between the two semi-permanently coupled units. Rounding out the appearance of the nominal 179-foot-long Super Turbine was either a 23,000- (UP Class 23C) or 24,000- (UP Class 24C) gallon insulated fuel tender recycled from old 800 and 3800 Class steam locomotives.

Under closer examination, the performance specs on these giants were nothing to snicker at, even in comparison to today’s motive power. The two-unit locomotives, costing about $845,000 apiece, tipped the scale at 849,248 pounds and could produce a starting tractive effort of 212,312 pounds with a continuous tractive effort rating of 146,000 pounds at 18 miles per hour. In comparison, GE’s modern high-tech ES44AC Gevo 4,400-hp diesel-electric, with its alternating current traction motors and radial steering trucks, weighs in at 432,000 pounds and is rated at a starting tractive effort of 180,000 pounds and a continuous tractive effort of 145,000 pounds.

Furthermore, outfitted with 40-inch diameter drivers and 74:18 gearing, the Super Turbines could reach a speed of 65 miles per hour while single-handedly hauling a consist of more than 100 freight cars across their usual Eastern District assigned routes. Occasionally seen doubleheaded with another turbine, the units were later retrofitted with MU controls for operation with diesel-electrics as trains continued to grow throughout the 1960s. Some members of the fleet were further upgraded, albeit temporarily, to a 10,000-hp rating.

Furthermore, outfitted with 40-inch diameter drivers and 74:18 gearing, the Super Turbines could reach a speed of 65 miles per hour while single-handedly hauling a consist of more than 100 freight cars across their usual Eastern District assigned routes. Occasionally seen doubleheaded with another turbine, the units were later retrofitted with MU controls for operation with diesel-electrics as trains continued to grow throughout the 1960s. Some members of the fleet were further upgraded, albeit temporarily, to a 10,000-hp rating.

Even during the delivery of these Super Turbines, though, UP realized that after several years of service, the small turbines were becoming too expensive to maintain despite their earlier praiseworthy performance. The use of heavy fuel oil took its toll on the fuel delivery systems and aided in turbine blade corrosion. A proper air filtration system, which could effectively stop the dirt and dust from entering the temperamental power plant without reducing efficiency too much, was never totally realized.

The development of higher-horsepower diesels, such as UP’s 6,600-hp DDA40X “Centennial” locomotives and the rising costs of one-time surplus Bunker C fuel further perpetuated the turbine’s demise. As maintenance costs finally started to exceed the operating costs of UP’s diesel fleet, the road’s bean counters began to sideline the turbine units. By the summer of 1964, the last of the 4,500-hp units were off the active roster with the Super Turbines remaining in service until the end of the decade. Super Turbine 7 had the honor of being the last Big Blow in operation, hauling its final consist on December 26, 1969.

Raising the Bar for HO Scale

While GE’s gas turbines were strictly a UP affair, the Super Turbines, in particular, have always been railfan favorites regardless of whether you were a Union Pacific follower — especially so once you’ve experienced ScaleTrains’ incredible HO-scale rendering.

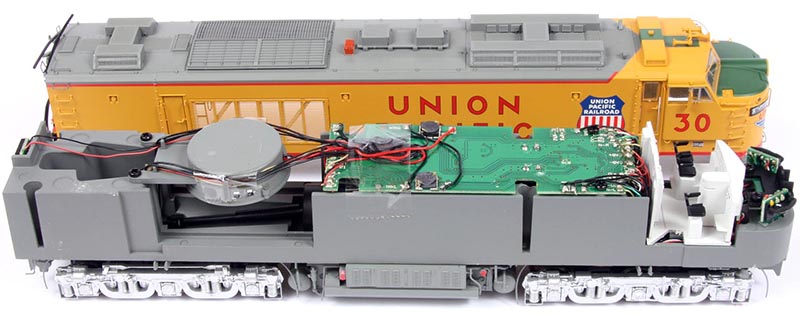

To begin with, I generally don’t mention packaging in my reviews, but Model Railroad News’ sample’s leather-clad box with its Museum Quality logo imprinted in gold on the lid is a classy touch and will be much appreciated by the collectors in our hobby. Inside, one will find the three individual units making up the 8,500-hp GTEL separately encased in typical clear plastic clamshell packaging that is then surrounded by shock-absorbing black foam. A color booklet is included as well with a short history of the prototype turbine program, as well as general operating and maintenance instructions. You’ll also receive Digital Command Control (DCC) function key descriptions and programming tips, and, most noteworthy, exploded views of each component of the HO-scale turbine, which display the numerous sub-assemblies and hundreds of separate detail parts going into each one of these models. Studying these later pages will certainly give one a better appreciation of the work involved in Big Blow’s production — simply remarkable!

The real power of the ScaleTrains’ piece doesn’t quite hit you until the model is unpacked and the three units are coupled together on the track. Measuring more than two feet in length, the Super Turbine rivals the UP’s other famous motive power, the 4-8-8-4 Big Boy steam locomotive, in sheer grandeur. With dial calipers in one hand and GE builder’s diagrams in the other, I commenced measuring the 1:87 model for scale accuracy. In the real world, the control unit measured 69-feet, 6-inches over its coupler pulling faces while having a distance between truck centers of 40-feet, 8-inches. Similarly, the turbine unit stretched 63 feet in length with truck centers at 34- feet, 2 inches apart. Both units rode on C-C type trucks featuring an axle spacing of 7-feet, 3-inches and 40-inch diameter drive wheels. In turn, the HO-scale model matched these critical dimensions inchfor- inch, forgoing the slightly oversized Type E metal knuckle couplers, as did our particular sample’s 23-C class fuel tender rendering to its prototype, which in its original form was once assigned to a 3800-series 4-6-6-4 Challenger.

Being of brand-new tooling, the injection-molded plastic carbodies display crisp molded-in details of the usual sort found on diesel-type hood and cab units — rivets, bolt heads, panel lines, vent openings, and the like. As already alluded to, though, the incredible number of separately applied parts is what really makes this model pop. While it has become part of the model railroad community’s vernacular to rate a newly delivered model by using an existing manufacturer’s brand, such as “Genesis” or “Proto” with the word “quality” in their description, I think we are about to see a new adjective added to the hobby’s vocabulary — “ScaleTrains quality.” The Super Turbine is just that good. The list of add-on parts is indeed long with many typical of higher- end pieces: wire hand grabs and railing; photo-etched walkways, platforms and grilles; all the various external plumbing, including sand lines extending down to the railhead; internal and external cab accoutrements; pilots dressed up with hoses and hardware; and so on, as are evident in the surrounding photos. However, it is the road number-specific details, in particular, that push this offering up and over the existing industry bar.

Being of brand-new tooling, the injection-molded plastic carbodies display crisp molded-in details of the usual sort found on diesel-type hood and cab units — rivets, bolt heads, panel lines, vent openings, and the like. As already alluded to, though, the incredible number of separately applied parts is what really makes this model pop. While it has become part of the model railroad community’s vernacular to rate a newly delivered model by using an existing manufacturer’s brand, such as “Genesis” or “Proto” with the word “quality” in their description, I think we are about to see a new adjective added to the hobby’s vocabulary — “ScaleTrains quality.” The Super Turbine is just that good. The list of add-on parts is indeed long with many typical of higher- end pieces: wire hand grabs and railing; photo-etched walkways, platforms and grilles; all the various external plumbing, including sand lines extending down to the railhead; internal and external cab accoutrements; pilots dressed up with hoses and hardware; and so on, as are evident in the surrounding photos. However, it is the road number-specific details, in particular, that push this offering up and over the existing industry bar.

When placed in a specific period within the fleet’s lifespan, each of the 30 Super Turbines exhibited unique visual characteristics, which ScaleTrains has taken full advantage of in showing off its rendering capabilities. First, as mentioned earlier, there were two different styles of fuel tenders utilized, UP 1–UP 20 receiving the 24,000-gallon 24-C class tenders of welded constructions and UP 21–UP 30 receiving the shorter 23,000-gallon 23-C class tenders with riveted panels, both of which the manufacturer has tooled up.

Next, all the control and turbine units featured multiple raised dynamic brakes housings along their rooflines — some forming an “H” shape and others an “I” with the first 15 units displaying an H-H + H-I pattern while the second group had an H-I + I-I arrangement. The manufacturer has addressed this attribute as well on its models.

Third, there are the changing air horn locations and extended fuel tanks on the control units to consider too. By the early 1960s, concerns over the horns freezing up, as well as their adding to the cab noise level caused the UP to relocate the air horns from the cab roof to a position over the hostling engine’s radiator grille. Also during this period, in an effort to keep the Super Turbines on the road longer, the diesel engine’s fuel tank capacity was increased by replacing the original rectangular tank with a larger more angular-appearing one that now extended out to the sides of the carbody. Meanwhile, over time, the grilles atop the control unit’s radiator section were toyed with as well, changing from a flat panel arrangement to a slightly raised louvered covering with some units exhibiting a mix of each style. Last but not least, the turbine units’ air intake housings could vary in design as well. The first 29 units, as-delivered, exhibited a more low-profile boxy design on their roofs, which on a number of units, over the years, was replaced with the more obtrusive-looking Farr Dynavane air intake system. Then there is UP 30, which was built with a one-of-a-kind intake system noted by its twin long air intake pipes extending out to the rear of the unit. Add to the mix the fact that fuel tenders and, on occasion, even the turbine units were changed out between locomotives over the years, and, well, you can see the challenges involved in the planning of this offering. Nonetheless, ScaleTrains has managed to pull it all off with great skill.

Third, there are the changing air horn locations and extended fuel tanks on the control units to consider too. By the early 1960s, concerns over the horns freezing up, as well as their adding to the cab noise level caused the UP to relocate the air horns from the cab roof to a position over the hostling engine’s radiator grille. Also during this period, in an effort to keep the Super Turbines on the road longer, the diesel engine’s fuel tank capacity was increased by replacing the original rectangular tank with a larger more angular-appearing one that now extended out to the sides of the carbody. Meanwhile, over time, the grilles atop the control unit’s radiator section were toyed with as well, changing from a flat panel arrangement to a slightly raised louvered covering with some units exhibiting a mix of each style. Last but not least, the turbine units’ air intake housings could vary in design as well. The first 29 units, as-delivered, exhibited a more low-profile boxy design on their roofs, which on a number of units, over the years, was replaced with the more obtrusive-looking Farr Dynavane air intake system. Then there is UP 30, which was built with a one-of-a-kind intake system noted by its twin long air intake pipes extending out to the rear of the unit. Add to the mix the fact that fuel tenders and, on occasion, even the turbine units were changed out between locomotives over the years, and, well, you can see the challenges involved in the planning of this offering. Nonetheless, ScaleTrains has managed to pull it all off with great skill.

Just take a closer look at MRN’s sample, UP 30. Looking beyond its wellexecuted paint and graphics job, which follows UP’s practices to the letter, the model has a story to tell. When it entered service in July 1961, the Super Turbine had its horn array over the cab; the aforementioned unique turbine air intake system; an H-I + I-I dynamic brake housing arrangement; a small fuel tank slung under the center of the control unit; and the 23-C class fuel tender trailing behind. The model also reflects these characteristics, with the exception of the control unit having the larger fuel tank, as well as the redesigned louvered radiator covering over one-half of its radiator section. As such, dated photos suggest the model best fits the appearance of UP 30 from about May 1962 through the summer of 1963, by which time the horns were relocated to the mid-section of the control unit’s roof. By 1968, UP 30 was showing up on the main line with a larger fuel tender, just a couple of years before it was officially retired from the roster on February 28, 1970. It was subsequently sold a year later to Nielsen Enterprises and then made its way to Continental Leasing before being scrapped.

Up to this point, my analysis has included attributes for both the Rivet Counter and Museum Quality versions of the HO-scale Big Blow. What’s further raising the bar for model railroading can be found in the Museum Quality offering, the details of which involve both the appearance and operational aspects of these models. On the detail front, the Museum Quality Super Turbine offers the addition of opening cab doors that even feature separately applied brass handles, as is the case for the non-opening compartment doors on the control and turbine units too. The turbine unit also boasts multiple sliding side doors, which offer a view of the simulated GE turbine and generator inside. Moreover, there are separate molded rubber MU and electrical bus cables, as well as radiator coolant hoses on the rear of the control unit. Finally, even the already well-appointed tender receives some enhancement in the form of truck safety chains.

Taking the Turbine out for a spin

When you are ready to take the Big Blow for a test drive, besides the flywheel-elequipped can motors and all-wheel drive and electrical pickup found in both the control and turbine units plus the directionally controlled LED headlights, tender backup light, and illuminated number boards outfitting both the DCC/ sound-equipped Rivet Counter (a DCCready version of the Rivet Counter Big Blow is also available) and the Museum Quality editions, the modeler will also discover a host of additional Museum Quality level special effects to operate. There are tri-color (red, green, and white) functioning class lights on the nose of the control unit, which may be manipulated via the F6 function key on one’s DCC controller.

Then you have the illuminated instrument panel, engineer’s side ground light, and a rear control unit walkway light that is used to great effect during the “Night Time Mode” function (F5). In addition, there is a motorized blade inside the exhaust hood of the turbine unit that spins when the turbine sound is engaged. Finally, even the incidental sounds are made to be more realistic with the addition of miniature sensors mounted on the trucks, which, when detecting locomotive movement through radius track sections or switches, activates the sounds of wheels squealing through the curves or the clunking of the trucks as they pass over the turnout frogs — a noteworthy first for the HO-scale market!

Equipped with a LokSound V4.0 decoder (Rivet Counter features LokSound Select decoders), our Museum Quality Super Turbine exhibited excellent speed control under DCC power with a sustained slow speed of less than one scale mile per hour and a maximum speed closely mimicking the prototype’s 65 miles per hour limit. I encountered no hesitation or jerkiness — just smooth operation even through minimum 22-inch radius curves. I usually report separate By-The-Numbers data for cab and booster locomotives, but since it wouldn’t be correct for the control and turbine units to ever be run separately and also due the fact that the motors and decoder settings in our samples were so well matched right out of the box, I believe the results of their operation in unison is suffice. The same goes for the drawbar test, where, individually, they may only rate average for an HO-scale diesel locomotive, but together they have an impressive capacity equal to 100-plus pieces of rolling stock on level track.

I did, however, encounter one operational anomaly during my test session and that involved the headlight. Right out of the box, MRN’s UP 30’s headlight never did function. I removed the shell and did a visual inspection of the small LED-equipped lighting board in the nose, as well as traced the wiring back to the main circuit board and didn’t uncover any suspicious-looking defects, such as a bad solder joint or loose or reversed wires, on which to blame the problem. A trip to the programming track for a review of control variable (CVs) settings didn’t reveal anything obvious to me either; it was time to contact the folks at ScaleTrains! Unfortunately, at the time this review went to press, no decoder-oriented fix for my predicament could be found, which suggested that perhaps I was looking at a defective lighting board or an assembly issue. Bottom-line, I’ll be taking advantage of the manufacturer’s generous two-year “bumper-to-bumper” warranty (when the consumer registers their product online) and sending our unit back for repair.

In the meantime, this relatively minor glitch didn’t hamper my “playtime” with the otherwise excellent-running Super Turbine in the least! I guess you would have to label me a sucker for the dramatic when it comes to sounds — the ScaleTrains Super Turbine is now the new king of the Model Railroad News test layout, even forgoing the largest of steam locomotive models! Things start off quiet enough under DCC as the units are initially addressed, cab lighting comes on briefly, and the instrument panel and number boards begin to glow. Then, the 850-hp diesel engine rumbles to life and the locomotive is ready to be coupled up to its consist. When ready to move out, pressing F3 engages the turbine and … It’s time to have your ear protection ready because these units are super-loud! It’s amazing just how much sound can be emitted from a 1.1-inch diameter speaker, but ScaleTrains, in partnership with LokSound, has done it and offers the modeler a pretty convincing audio experience for which these units earned their “Big Blow” nickname. I see now why they were kept away from operating around large urban areas!

In the meantime, this relatively minor glitch didn’t hamper my “playtime” with the otherwise excellent-running Super Turbine in the least! I guess you would have to label me a sucker for the dramatic when it comes to sounds — the ScaleTrains Super Turbine is now the new king of the Model Railroad News test layout, even forgoing the largest of steam locomotive models! Things start off quiet enough under DCC as the units are initially addressed, cab lighting comes on briefly, and the instrument panel and number boards begin to glow. Then, the 850-hp diesel engine rumbles to life and the locomotive is ready to be coupled up to its consist. When ready to move out, pressing F3 engages the turbine and … It’s time to have your ear protection ready because these units are super-loud! It’s amazing just how much sound can be emitted from a 1.1-inch diameter speaker, but ScaleTrains, in partnership with LokSound, has done it and offers the modeler a pretty convincing audio experience for which these units earned their “Big Blow” nickname. I see now why they were kept away from operating around large urban areas!

In addition, I was especially happy to see that both powered units have speakers too so that the proper sounds actually emanate from the appropriate source. Sound the playable horn, which is an actual recording of the Leslie S5T-RF horn with which the real Super Turbines were equipped, and your train is ready to move out. Also worth noting are the authentic GE bell, dynamic brake sounds, and coupler clank, the sanding valve, and short air let off that may be manually controlled through the F1, F4, F9, F11, and F12 function keys, respectively. Simply put, well done.

Shock and Awe

Between its immense size, incredible level of detail, and thunderous sounds, this is an amazing release! Scale Trains Museum Quality Big Blow brings on shock and awe to the HO-scale world. Perhaps it is becoming too much of a cliché to state that a new model offering “raises the bar” for the hobby, but, in fact, the Super Turbine does so — undeniably. Yes, the Museum Quality version is pricey, but the manufacturer has shown that, if a modeler is willing to pay for all the detail and operating features they truly desire, this company is quite capable of delivering it. I do believe ScaleTrains now has our full, undivided attention!

ScaleTrains HO-scale Museum Quality

GTEL 8,500-hp turbine locomotive with DCC LokSound

Union Pacific No. 30

#SXT70004, MSRP: $774.99

ScaleTrains.com, Inc.

7598 Highway 411

Benton, TN 37307

844-987-2467