by David Otte/photos by the author except where noted

by David Otte/photos by the author except where noted

As is often the case with generalities made in this hobby, I’ve heard many a railfan more than a few times refer to any Electro-Motive Division (EMD) bulldog-nosed four-axle diesel they lay their eyes on as nothing more than an “F-unit.” While harmless in passing, not all F-units are created alike! Sure, the FT, F3, F7, F9, FP7, and FP9 models can be a little confusing at times with their seemingly common lengths, porthole side windows, and often similar style carbody grilles and vents. However, to the trained observer, the differences are not subtle in the least. Case in point, take a closer look at the two latter variants designated by EMD, in particular, for passenger service. The FP7 and FP9 are actually four feet longer than their brethren and can almost be considered hybrids — a cross between their freight family heritage and six-axle E-unit cousins — which EMD specifically designed for hauling passenger consists.

Luckily for us HO-scale modelers, we have an excellent example of the prototype to study in the form of Athearn’s Genesis-level FP7 diesel locomotive model. Recently, the manufacturer delivered a new run of these locomotives as single units and, as appropriate for the railroad, paired up with either an FP7A/FP9A cab or F7B/F9B booster unit. Three different paint schemes are currently available, including Ferrocarriles Nacionales de México (N de M), St. Louis-San Francisco (Frisco), Southern Pacific (SP), and Amtrak. Furthermore, announced road names coming down the pike in 2017 will include Burlington Northern (modified for freight service and BN-patched Northern Pacific passenger schemes), Northern Pacific, Chesapeake & Ohio, and Pennsylvania Railroad. As usual, the modeler has the option of purchasing units in several different road numbers, as well as choosing factory-installed Digital Command Control (DCC) with SoundTraxx sound or DCC-ready versions.

Amtrak livery was not quickly applied, nor did it cover all the early motive roster of the 1970s. This September 1973 shows a pair of Amtrak diesels still wearing original owner paint schemes. Southern Pacific 6455 is Amtrak’s 118 officially at this point. Behind it is an Amtrak E-unit in Union Pacific colors. Athearn’s Genesis FP7 release includes SP models detailed similar to this example. —Dave Stanley photo, Kevin EuDaly collection

F-unit Genealogy

To best appreciate the Athearn FP7 rendering, we need to provide a little context for the prototype and how it fits into the bigger picture of early dieseldom. We begin by traveling back to November 1939 and the birth of the first beloved F-unit when a four-locomotive set rolled out of Electro-Motive Corporation’s La Grange, Illinois, plant and began a national tour. Two cab units with that now highly recognizable bulldog streamlined nose, designated “A-units,” and two boosters without cabs, called “B-units,” were coupled together to form one powerful locomotive.

Equipped with the relatively new 16-cylinder, 567-series prime mover, each FT unit could provide up to 1,350 hp and attain speeds of 75 miles per hour. A unique streamlined cowl-type body housed the power plant. Whereas hooded locomotives such as GP7s or RS-3s relied on the strength of their underframes or decks to support them, the FT design depended on its steel truss superstructure for strength. Furthermore, the covered body design of the FT allowed for crewmembers to service the locomotives under protection while the train was in motion, as well as for providing safer movement between units.

With the FT also came the introduction of the famous Blomberg truck. This two-axle truck was equipped with traction motors geared to each axle providing for all-wheel drive. The Blomberg truck would become a standard for EMD-built four-axle locomotives for years to come. The practice of coupling multiple units together to form one locomotive came into being with the FT. For example, it was quite common for railroads to order FTs in semi-permanently coupled sets of A-B units providing 2,700 hp. These A-B sets coupled in an A-B-B-A arrangement could provide a train with 5,400 hp, and, with cabs at either end, crews never needed to turn the locomotives, as was necessary with steam locomotives. Generally, the FT was a freight locomotive, but the B-unit could be equipped with a steam generator to provide steam heat for passenger service too.

After the initial success of the FT (and now a full division of parent company General Motors), Electro-Motive Corporation further refined its popular locomotive, introducing the F2 and F3 editions beginning in 1945, as well as offering the F7 variant by early 1949. With approximately 2,370 cab units and 1,480 booster units sold, the F7 was the best-selling model of the famous “covered wagon.” This version featured an up-rated V16-567B prime mover and electrical gear, which produced 1,500 hp and 56,500 pounds of tractive effort, all packed inside a slightly modified carbody that maintained the same handsome bulldog nose styling. Some 50 different U.S. and Canadian railroads purchased F7s, utilizing them in both freight and passenger service. Production of the F7 lasted until December 1953 when EMD introduced the final version of the F series, the 1,750-hp F9.

January 1976 finds a pair of FP7s running off their final miles. Originally delivered to Southern Pacific, Amtrak acquired the remaining 14 of the 16 original SP FP7s during the passenger carrier’s early days of the 1970s. Amtrak numbered its FP7s (110–123), after a group of Burlington Northern F7As that started at 100. —John Arbuckle photo, Kevin EuDaly collection

It’s All About the Water

As popular as it was, the F-unit as such did not quite meet the demands of all EMD’s railroad customers, most notably in passenger service. While the builder’s E-unit possessed a design specifically for this job, railroads traversing tough terrain desired the sure-footed F-unit for hauling passenger consists, where the higher weight-to-drive-axle ratio was a big plus. True, the popular F7 and E8 models had roughly equivalent starting tractive efforts of 56,500 pounds each, but the four-axle, four traction motor equipped F-unit had a continuous tractive effort almost 10,000 pounds higher, at 40,000 pounds, than its six-axle kins with only four traction motors. There were also those roads that only had short-haul passenger runs to worry about and wished to utilize their cab units in dual service. Nevertheless, the common factor in all these cases, though, was steam generator water capacity.

Steam was required for both heating and cooling (through steam ejector air conditioning) passenger cars during this time period, and it was up to the motive power to provide an ample supply. As alluded to earlier, steam generators were an option on the F-units, with the roomier booster the logical choice for its location, although several railroads ordered both F3 and F7 cab units so equipped too. It’s not that the builder couldn’t fit an ample steam generator in the latter, but the space for the boiler’s associated water supply tanks was the real issue. For railroads operating in areas with particularly colder winter climates, the volume of water used for steam could be substantial, requiring frequent time-consuming stops to refill.

According to EMD manuals, boiler water capacity on a cab unit equipped with a minimal 1,600-pound-per-hour steam generator was limited at best to 1,300 gallons. This type of F-unit included a 200-gallon tank housed beneath the steam generator at the rear of the carbody, plus a 500-gallon tank situated behind the cab and a 600-gallon hatch tank situated above in the roof. Of course, this area behind the cab was also the space taken up with the optional dynamic brake equipment and, for those roads going with this option, the water capacity drops down to only the 200-gallon boiler tank. Furthermore, if a railroad employed the larger 3,000-pound-per-hour steam generator, then the 200-gallon tank would be eliminated too.

This early 1976 image shows Amtrak 111 leading another FP7 at Port Chicago, California. The trailing FP7 still wears SP’s Bloody Nose scheme with Amtrak number, 118, and the service’s name stenciled in white. Athearn’s new Genesis model is detailed and decorated to match this 1970s look for Amtrak’s FP7 in Phase I paint. —John Arbuckle photo, Kevin EuDaly collection

The booster units fared slightly better with a 1,200-gallon vertical tank located in what would have been the cab compartment, a 600-gallon hatch tank (if no dynamic brakes), and possibly a 200-gallon tank beneath the boiler, depending on the size of the steam generator. In comparison, an E8A, often equipped with twice the steam generator capacity, could handle 1,950 gallons of water without dynamic brakes and 1,200 gallons with the option, while E8Bs carried 3,150 gallons or 2,400 gallons of water, respectively.

Of course, some roads found workarounds. Santa Fe, for example, equipped its F7As with water tanks and steam controls only (instead of steam generators) to supply a greater amount of water to the boilers in the B-units. Southern Railway relocated the usual underbody air reservoir tanks on its F-units to their roofs and slung 1,200-gallon water tanks beneath. Other roads looked to EMD for a better solution for this situation.

In mid-1949, EMD answered the call with the FP7. EMD stretched the F-unit carbody and frame some 48 inches between the first porthole side window and first carbody vent to create its new FP7. The new F-unit design could maintain dynamic brakes, while also including an 820-gallon vertical tank, a 330-gallon hatch tank behind the dynamic brake’s cooling fan housing, and a 200-gallon tank beneath the boiler of either the newly specified 1,800- or 2,750-pounds-per-hour steam generator. A 3,900-pound-per-hour unit was also an option, but negated the small tank. Furthermore, additional capacity in the form of a 600-gallon hatch tank was an option in lieu of dynamic brakes. This arrangement offered the FP7 an overall water capacity of 1,850 gallons without dynamic brakes and 1,350 gallons with dynamic brakes — both totals comparing closely with that of the E8A. There was even an option for an additional 280-gallon transversely mounted underframe tank. EMD never cataloged an FP7 booster unit. The diesel builder promoted its steam-generator F7B model as possessing adequate water-carrying capacity as a companion for the new cab unit.

Purchasers of the F-unit intending it for passenger or dual service could finally have their cake and eat it too! Rock Island would be the first to place an order for 10 of EMD’s FP7s. These Rock Island FP7s were delivered starting in June 1949. EMD’s largest customer for its stretched F-unit was Louisville & Nashville with 45 FP7s, followed closely by Atlantic Coast Line’s 44 and the Pennsylvania Railroad’s 40 units. By the time Alaska Railroad’s three FP7s rolled off the production line in December 1953, EMD had erected some 301 units for 24 domestic roads. Additional export sales accounted for 21 more FP7s, while EMD’s Canadian counterpart, General Motors Diesel (GMD), built 57 for north-of-the-border roads. In early 1954, the FP7 was replaced by the FP9, which was entirely produced for the Canadian and export markets (Chicago & North Western did have a couple of its FTs rebuilt by EMD to FP9 standards, though, albeit with only a 1,500-hp rating). Nonetheless, they racked up an additional 86 units for the stretched F-unit design, bringing the total number of FP7/FP9s constructed to 465 by the end of 1959.

Athearn’s Genesis FP7

Athearn’s Genesis F-unit series is well known among modelers as being one of — if not the very best — representations of the EMD cab unit design on the HO-scale market today. The FP7 is no exception to this high praise. Dressed in early Amtrak colors, our sample FP7 numbered 111 is a real head-turner in many ways.

To begin with, let’s talk details. After all, that’s the major factor with Genesis line models. To discuss this Amtrak unit, though, we’ll need to trace its heritage back to the FP7’s original owner: Southern Pacific. Amtrak 111 is formerly SP 6447, serial number 18131 — one of 16 FP7s (numbers 6446–6461) delivered to the railroad between February and May 1953 at a total cost of more than $3 million. As such, both the prototypes and MRN’s particular Athearn rendering have the typical spotting features of Phase II production units. These features include vertical louvered carbody vents and vertical openings in the stamped grilles above, as manufactured by the Farr Company, plus the late Phase II’s larger 48-inch diameter dynamic brake cooling fan on the roof. This is in contrast to the horizontally oriented louvered vents and built-up side grilles and 36-inch dynamic brake fans of the Phase I FP7s.

From their build date to August 1972, when the National Railroad Passenger Corporation purchased the surviving units (two SP FP7s had been wrecked and scrapped by this time), SP’s FP7 fleet went through a bit of a transformation that altered their physical appearance to the one we see displayed on Athearn’s HO-scale model. When they initially arrived on the scene, the units displayed multiple-unit (MU) connections on their front pilots and an MU door on the nose above. These FP7s also sported front- and rear-end mounted lifting lugs, an oscillating signal light with dual-sealed beam headlight mounted in the nose door, dynamic brakes, a high-capacity 4,500-pounds-per-hour Vapor Corporation steam generator, and only partial side skirting. These units were ordered with larger 1,500-gallon fuel tanks that extended the full width of the carbody. SP did not opt for the additional 280-gallon underframe water tank, but its FP7s did come with the standard 820-gallon vertical and smaller 330-gallon hatch tanks. Sheet metal sunshades above the cab side windows and a Nathan M5 air horns offset to the engineer’s side of the cab roof rounded out these FP7’s as-delivered look.

From their build date to August 1972, when the National Railroad Passenger Corporation purchased the surviving units (two SP FP7s had been wrecked and scrapped by this time), SP’s FP7 fleet went through a bit of a transformation that altered their physical appearance to the one we see displayed on Athearn’s HO-scale model. When they initially arrived on the scene, the units displayed multiple-unit (MU) connections on their front pilots and an MU door on the nose above. These FP7s also sported front- and rear-end mounted lifting lugs, an oscillating signal light with dual-sealed beam headlight mounted in the nose door, dynamic brakes, a high-capacity 4,500-pounds-per-hour Vapor Corporation steam generator, and only partial side skirting. These units were ordered with larger 1,500-gallon fuel tanks that extended the full width of the carbody. SP did not opt for the additional 280-gallon underframe water tank, but its FP7s did come with the standard 820-gallon vertical and smaller 330-gallon hatch tanks. Sheet metal sunshades above the cab side windows and a Nathan M5 air horns offset to the engineer’s side of the cab roof rounded out these FP7’s as-delivered look.

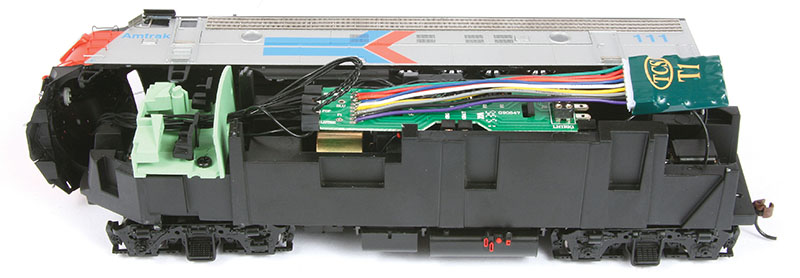

I couldn’t resist installing a decoder in our DCC-ready sample and found the procedure quite simple thanks to Athearn’s “Quick-Plug” feature — it’s truly plug-n-play. Also visible here are the famous Genesis driveline with “dynamically balanced” five-pole skew wound motor and dual flywheels and its constant directional lighting system. Although Athearn is still using incandescent bulbs, they do offer a more realistic glow than many of the LED-equipped locomotives I’ve experienced.

By early 1957, changes were in the works. First, snowplow pilots began to appear on the units. Research shows all were so equipped by 1968. Next, while this feature was being installed, the recently government-mandated handholds on the nose and the railing above the windshield for accessing and maintaining the windshield were being implemented. Usually, most railroads located the hand grabs on the right or engineer’s side of their cab units, but SP chose to add them to the left side, offering its FP7s a more distinctive appearance versus other roads. Finally, the addition of the icicle breaker bars atop the cab and rear carbody came in 1964-65. They were designed to protect not only the road’s passenger dome cars, but the equipment mounted on top the locomotives as well. Their rooftop location, however, does vary from unit to unit with some FP7s having the front breaker bars directly over the cab; others had them positioned further back behind the cab. In addition, some units, but not all, had what little side skirting was present when new removed. Together, these are the visual characteristics of the FP7s inherited by Amtrak.

Paint and lettering style on these units changed over time as well. When delivered, SP was using its attractive Black Widow paint scheme. This color combination soon gave way to the Bloody Nose scheme, which displayed a Dark Lark Gray carbody with Scarlet Red nose. Although adopted in 1958, the FP7 fleet didn’t receive the new colors until sometime between 1961 and 1964. This scheme would last until the surviving units went to Amtrak in 1972. Even then, however, a number of the units continued to appear in Bloody Nose paint and exhibit their SP road numbers for a few years thereafter, some FP7s never receiving Amtrak paint at all.

From this angle, we can enjoy the nicely detailed rooftop cooling fans that have been expertly reproduced on the Athearn Genesis FP7. Note the delicate vanes of the grille and the separate fan blade beneath. Also present on the Amtrak unit to take in and appreciate are the delicate molded-in bolt heads outlining each rooftop hatch and the add-on metal lift rings and icicle breaker bars, the latter of which is a remnant of its former owner, Southern Pacific.

Amtrak 111 was still wearing its old SP colors as late as August of 1973. It wasn’t until sometime after the summer of 1973 that this FP7 received the colorful Amtrak Phase I paint treatment with large “pointless arrows” displayed on its sides. The fleet operated pretty much as it did before its purchase on various SP passenger train routes. Amtrak’s FP7s could be seen as far east as Louisiana on the Los Angeles–New Orleans Sunset Limited and as far north as Washington state on the head end of the Los Angeles–Seattle Coast Starlight. These units pulled Amtrak’s resurrected San Joaquin, running between Oakland and Bakersfield, California, and could be found on the lead of the specially chartered Reno Fun Train out of the Bay Area and over the grades of the picturesque Sierras. Occasionally, the FP7s were spotted even working the western end of the Oakland–Chicago San Francisco Zephyr. Besides operating in typical F-unit cab and booster configurations, the FP7s could also be found MUed with Amtrak’s SDP40Fs, new F40PHs, and with various helper freight locomotives supplied by the railroads over whose tracks Amtrak traveled.

Unfortunately, the writing was already on the wall for these aging EMD cab units, when they joined Amtrak in the early 1970s. By early 1975, Amtrak had scrapped two members of the fleet with another eight sent to EMD as trade-ins on new F40PHs, which would begin showing up on the former SP passenger routes within a year. This left just four units, (111, 116, 117, and 123), which were renumbered into the 375–378 series by the summer of 1976. Depending on which source you read, things get a little hazy at this point regarding the future of former 111. Based on my research, I believe two units, 375 (ex-111) and 378 were promptly retired only a few months later and traded in on more F40PHs (and, no doubt, subsequently scrapped), leaving only 376 and 377 to be renumbered yet again as 492 and 493. Finally, the former 116 and 117 would meet their demise from the scrapper’s torch as well in May 1980.

The Athearn Genesis HO-scale model of Amtrak 111 conjures up all these memories of the prototype while still in early Amtrak service with its well-executed paint and graphics application and outstanding road number-specific details that even matches the icicle breaker bar placement that existed on the actual SP 6447/Amtrak 111. The overall quality of assembly of our sample was also commendable with no signs of unsightly glue residue or other evidence of sloppy workmanship. All the separately applied parts, in particular, make this model live up to the Genesis name and then some. Those parts include the plethora of wire grabs and railings, photo-etched carbody grilles, windshield wipers, and the steam generator exhaust vent. Additionally, the cab side rearview mirrors, flush-fitting window glazing, painted cab interior, delicate vanes of the see-through cooling fan housings, and ample pilot details live up to the Genesis reputation. The appropriate SP-style rooftop accoutrements and the retained side skirting add to this model’s authentic appearance.

Part of the Genesis’ favorable reputation came from excellent operation. Athearn’s FP7 diesel locomotive model fails to disappoint. The flywheel-equipped, all-wheel drive mechanism found powering this DC-ready sample was silky smooth with no break-in period required. Thanks to Athearn’s DCC Quick-Plug setup, installing a motor decoder for digital control and silent running is a breeze. I used a Train Control Systems’ T1 decoder without wiring harness to test MRN’s model and couldn’t have been more pleased with the enhanced performance that DCC offered this already exceptional running conventional locomotive.

Not Just Another F-unit

Athearn’s Genesis FP7 isn’t just another F-unit model. As my closer examination of the model reveals, it’s a high-quality piece characterized by accurate road-specific details with high-end decoration and the usual quality Genesis drivetrain.

Athearn HO-scale

EMD FP7 diesel locomotive DCC-ready

Amtrak (Phase I)

#G22579, MSRP: $189.98

Athearn Trains

1600 Forbes Way Suite 120

Long Beach CA 90810

(310) 763-7140

This review appeared in the January 2017 issue of Model Railroad News