by Tony Lucio

by Tony Lucio

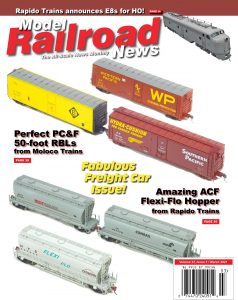

I never expected to begin a review by sharing a hearty chuckle obtained from the subject’s instruction sheet. Yet in the second sentence introducing its latest new freight car model, Rapido’s statement “We’re really proud of this thing…” is both refreshingly lighthearted and objectively accurate. How so? For 50 years model railroaders have enjoyed an odd rite of passage — upon first encountering a certain model once tooled by Roco and sold by AHM, confusedly asking “What the heck is this… thing?” For most of that time, the answer vis-à-vis the prototype was somewhat elusive. Even worse, once the prototype was known it was even harder to reconcile with the model. Plagued by an identity crisis of mixed labeling, botched details, and exclusively inaccurate paint jobs, that old AHM-Roco “thing” was nonetheless supposed to represent one of railroading’s most significant evolutionary freight cars: the first Pressure Differential (PD) hoppers developed and built by American Car & Foundry (ACF). Upon its release, ACF’s PD hopper was, somewhat more memorably, marketed to on-line customers as the “Flexi-Flo” by its development partner and sole buyer, New York Central Railroad (NYC). Yet beyond its strange appearance, the “Flexi-Flo” ACF PD3500 is an important transitional design for several reasons, some of which are apparent by study of its unique shape. However, to better appreciate this significance — and perhaps the confusion that dogged the infamous AHM-Roco model — we must rewind to a few years prior to its release.

“CenterFlow” is a well-known trademark among railfans and modelers, and normally recalls smooth-sided covered hoppers with a nominally teardrop-shaped cross-section. The term originates from ACF’s marketing of its patented design for a covered hopper with no internal center sill that might otherwise obstruct the lading compartments and outlet bays. This revolutionary breakthrough — afforded by ACF’s prior expertise designing and fabricating tank cars — removed interior nooks and crannies that retained cross-contaminate lading and allowed more efficient unloading. Yet while the smooth “flat-curved” sides of a teardrop cross section are perhaps the most defining visual characteristic of a CenterFlow hopper, when ACF first unveiled and branded them in 1961 they were strictly cylindrical in form: as such, the CenterFlow’s inspirational development link to tank cars is obvious. While the cylindrical design rapidly proved its value, ACF and railroads alike believed further efficiencies could be gained where certain commodities were concerned. ACF’s research and engineering departments thus went to work in pursuit of more efficient unloading methods and carbody shapes. Those two initiatives came together in August 1964 for the 3,500-cubic-foot Pressure Discharge (PD3500) CenterFlow, or “Flexi-Flo” hopper.

ACF’s PD3500 bore two significant evolutionary traits over its cylindrical CenterFlow predecessors. The most obvious — depending on which side of the car you were on — was the complex plumbing arrangement for internally pressurizing the car with air up to 15 psi, and discharging its contents to a transloading vessel. Pressurizing the car allowed dense commodities such as concrete and limestone to be rapidly discharged, and assisted with flushing the car clean between loads. The sealed-outlet pneumatic transloading capability — first developed and unveiled as an option for cylindrical CenterFlows in 1962 — was a feature NYC planned to heavily leverage in promoting the cars to its aggregate material customers in the northeast. The “Flexi-Flo” name coined by NYC echoed the contemporary “Flexi-Van” branding used for its intermodal equipment innovations; NYC meant both services to highlight customer-oriented offerings in an era bitterly competitive against other railroads and upstart highway carriers. The PD3500’s second evolutionary tell was subtler and best seen via the end view, where its cross section could be seen as less cylindrical, and slightly more tear dropped in shape. ACF seemingly realized that while a cylinder was inherently strong, flattening its lower sides from the midpoint to the side sills was an obvious way to obtain more cubic volume. Yet as the durability of such a form was not yet proven and the car was intended for dense, heavy loads, ACF braced the lower sides with a series of ribs, almost as if a standard cylindrical body were in a cradle of sorts.

Thus, at a first viewing, the PD3500 might be perceived as a classic cylindrical hopper with a bunch of strange plumbing and a curious lack of end cages at the platforms. Yet, if you were to add the end cages and subtract the outlet plumbing and sidewall ribs, you might be surprised to discover a car more like what we typically think of as a “traditional” CenterFlow hopper. Indeed, while the Pressure Differential car was in development, ACF was also working on its largest standard (non-pressurized) CenterFlow to date. Unveiled in October 1964 at a whopping 5,250 cubic feet, that car abandoned the upper cylindrical shape for an even flatter and more voluminous “teardrop” section. That profile would ultimately define all future CenterFlow hopper production in all capacities, toward becoming the now-classic shape most railfans associate with the term “CenterFlow.” Notably, that same essential shape was also used for subsequent PD hoppers which were developed in 1966 and afterward, even as their extra plumbing remained like that on the Flexi-Flo.

So ACF’s “Flexi-Flo” PD3500 hopper is not just a visually perplexing oddball, but a captivating example of laboratory R&D briefly unleashed to the outside world, with visual cues linking trends that came before and afterward. In a similar way, we can look back on the old AHM-Roco model to understand where its “mislabeled” (though not entirely inaccurate) CenterFlow branding came from, while recognizing its shortcomings as a product of a simpler time, and turning our gaze to the revolutionary models Rapido has finally brought to us all this time later.

ABOVE: Introduced in 1964, ACF’s Pressure Differential or PD hopper was a watershed prototype whose unique design became interlinked with the “Flexi Flo” service branding developed by buyer New York Central. The original 25 cars built in 1964 featured unique vertical braces on the lower carbody side. The pneumatic tubing plumbed below the side sill was another immediately captivating feature.

Plenty Different and Worth the Wait

I’ll cut right to the chase with the question most of you are probably asking: is Rapido’s new Flexi-Flo worth the wait? As someone who kitbashed one of the original AHM models into a more respectably accurate rendering in 2009, and found the undertaking to be enormously difficult, I can unequivocally and emphatically state yes! Rapido’s new models don’t merely address the old model’s numerous and obvious shortcomings, they lavish heaps of additional details that even the most ardent Flexi-Flo fans — including those dedicated to upgrading the old models — would likely not have understood or known about or bothered to pursue. In typical Rapdio fashion multiple variants are offered too, so let’s get down to the details.

New York Central accepted the first order of 25 PD3500s in August 1964 and gave them the classification 941-H. Numbered 885800–88524, the 941-H cars featured distinctive sets of vertical ribs on the lower carbody, and three 24-inch round hatches on the roof. These early cars were rated for 100 tons and bore a silhouette unmistakable for anything else: their exposed end platforms featured prominent shepherd’s hook or “lollipop” hand holds at the corners. The B-end displayed stacked brake and pressurization reservoirs plumbed in a semi-exposed rat’s nest unlike any other car on the rails. Plumber intrigue wasn’t reserved for the B-platform either, as one side of the car exposed another array of piping and valves beneath the side sill, connecting each of the four outlet bays to pressurization and discharge lines. Painted in ACF’s factory “hopper gray,” NYC’s snazzy “Flexi Flo” branding splashed Jade Green on the center of the upper curved flanks, while the road’s classic cigar-band herald was on the right side of the car.

Pleased with the new cars, NYC returned for more PD3500s which were delivered in two subgroups. Both featured a revised carbody structure that traded the sets of vertical ribs for two long horizontal beams, enlarged the rooftop hatches to 28 inches, and increased the rated capacity to 125 tons with new trucks and larger wheels. These cars were among the heaviest then rostered by NYC, which somewhat explained the exotic brake valve arrangement. The first batch of these variants was delivered in 1965 and classified 963H, with numbers 885825–885899. The second and final batch of 120 cars — more than half of total PD3500 production — was delivered through August 1966 as numbers 88680–88799 and classified 996H; they differed only in having the sides fabricated from six separate panels instead of three. Rapido offers each ACF PD3500 carbody type with its unique traits, in a variety of paint schemes. (To further illustrate the point that “Flexi Flo” was a railroad marketing term and not an official ACF moniker, it’s worth mentioning that another type of hopper, the PD3000 built by North American Car Company, received the Flexi-Flo branding under NYC successor Penn Central (PC); 110 were built for PC in 1974 with boldly updated “Flexi-Flo” graphics even though they looked nothing like ACF’s PD3500 design.)

ABOVE: Compare the reservoir tanks on the later (horizontal beam) PD3500s to those of the early cars as seen on page 34. The overall plumbing arrangement is mostly the same but has a few subtle tweaks. Also note the lowered brake wheel and solid end platforms. Rapido’s paintwork on all schemes is excellent and the fine text on the ends of the car is fully legible.

That this is a 21st century model is evident immediately upon removing the model from its plastic snap-tray box and witnessing its finely perforated etched-metal roofwalks, formed to the proper contour, and elevated with appropriate standoffs. Even more importantly, modelers who have researched the prototype will greatly appreciate the correct circular roof hatches with excellent detail relief and proper spacing. The B-end is embellished with a classic screen saver brought to 3D life: the dual reservoirs and oversized valves are plumbed with a mesh of fine wire that begs for visual tracing; the transverse platform access handhold only adds to the visual intricacy. The early “941H” and later “963H/996H” cars have differing arrangements; the former used two identical medium-size reservoirs while the latter had function-specific reservoirs of different sizes (one larger, one smaller) and modified plumbing. Another interesting quirk of the early cars is their taller brake wheel pedestal, which required an additional screen mesh “stepstool” platform. Later cars used a standard brake pedestal and did not need the stepstool. All models feature finely rendered lollipop grabs at the platform ends – to anyone who was ever puzzled by corner obelisks on the old AHM model, the importance of this signature detail cannot be overstated. Amazingly, these delicate details are more durable than they look: I gently pressed a few and was able to deflect them in a flexible bend about 5 to 10 degrees off plumb, with no adverse effects.

Rapido Trains

rapidotrains.com