NYC’s “Niagara” Comes to Life in BLI’s HO Rendition

NYC’s “Niagara” Comes to Life in BLI’s HO Rendition

Review by John Sipple/May 2005 Model Railroad News

Broadway Limited Imports has added to its impressive catalog of locomotive accomplishments with the introduction of their New York Central 4-8-4 “Niagara” steam locomotive. They are offering roadnumbers 6001, 6017, and 6024 (plus a painted, unlettered version) in your choice of a QSI-Sound/Analog d.c./DCC equipped version or a no-sound or decoder/DCC-ready version.

New York Central’s “Niagara”

When World War II ended in early September 1945, everything had changed. The American economy had held its breath, first during the long, terrible decade of the Great Depression and then through another half decade of war. For ten years, the consumer couldn’t afford to buy new things, then during the war, he had the money but products were rationed. The railroads were consumers, too – of locomotives, among other things.

Sunday River Productions

Just as the American housewife plotted the day shed could buy new appliances, so the New York Central’s chief engineer of motive power Paul W. Kiefer planned the post-war locomotive fleet. Paramount in his plans was a new class of steam locomotives, high-speed power to place on the point of the Central’s crack New York-Chicago trains. So in 1945, he handed over the design plans to Alco’s Schenectady, N.Y., facility and 27 brand-new 4-8-4 locomotives emerged. Number 6000 was in a class of its own, S1a, as the pilot model, and sister 5500 (class S2a) was a specialized version with poppet valves on the cylinders.

Number 6001 to 6025 represented Class S1b, the pinnacle of steam locomotive development. Virtually everything on these locomotives had appeared on other Central steamers. The pedestal 14-wheel tenders had been found behind 4-6-4 and 4-8-2 versions and had proved to be superior in many ways. They had special vent designs which allowed them to take water through scoops from between-the-rails track pans at speeds twenty miles per hour faster than earlier tender designs. “Elephant eared” smoke deflectors had already been seen on the 4-8-2 Mohawks. Scullin and Boxpok drivers had joined with roller bearings on both Mohawks and Hudsons so, in many ways, the mighty 4-8-4 was just an off-the-shelf power upgrade.

But collectively, it was more than that. After the practice of the New York Central to name its locomotives after rivers and Indian tribes, they uncorked the image of the state’s most spectacular sight, Niagara Falls. The rushing, thundering 4-8-4 would be named the Niagara. The 4-8-4 type had more names than a carnival conman, anyway, so this one seemed especially appropriate. Like the famous GS-4 Daylight 4-8-4s of the Southern Pacific, the Niagara had an airhorn as well as whistle.

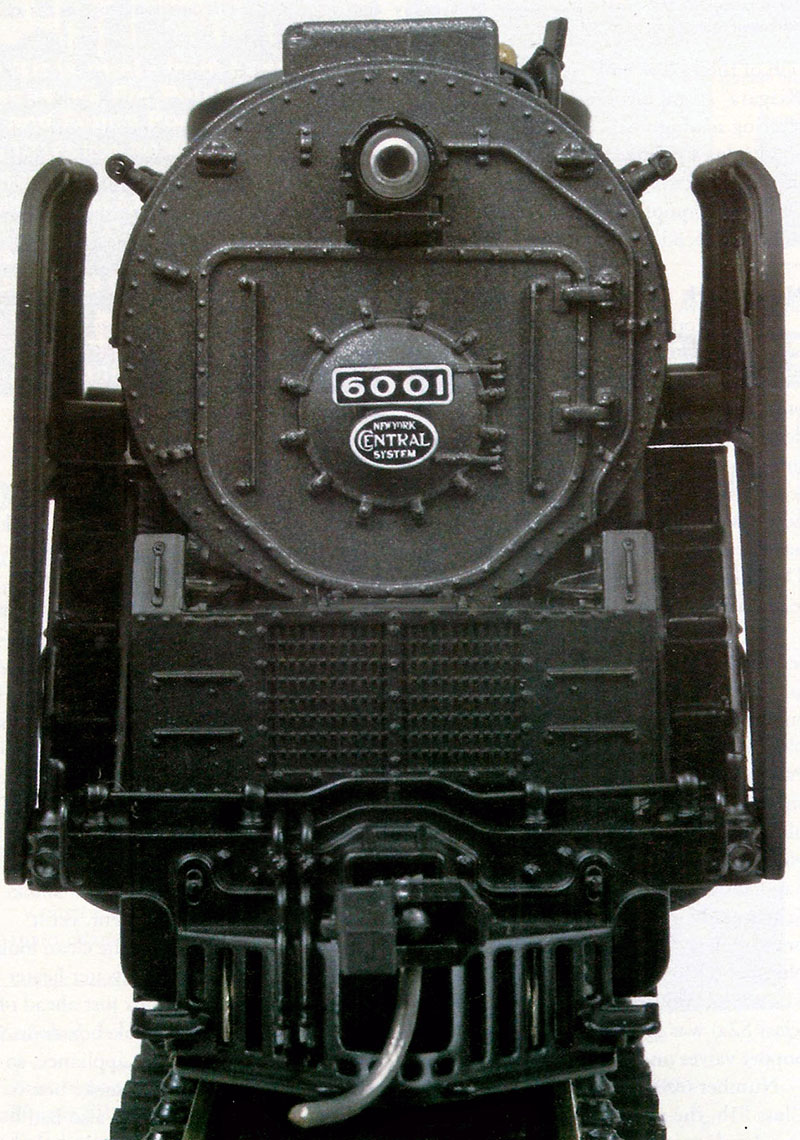

Every designer stamps his own brand on his plans, and Kiefer’s postwar smoke box face was certainly different, yet it made great sense. He like the clean look of the Worthington SA feedwater heater which jutted up a small box just ahead of the stack, but a normal smokebox door would be restricted by that appliance, so he lowered the door in the smoke box face. Mohawks with this face also had the headlight mounted on the door, but the Niagara found it placed higher up on the face, though not all the way to the top. It filled the empty space and gave the entire design an appealing look.

New York Central 6016 at Harmon, N.Y.,William D. Volkmer photo

Broadway Limited Import’s “Niagara”

Broadway Limited Import’s “Niagara”

As a model, this one also has an appealing look. The face is unmistakable; from the railheads to the top of the feedwater heater, this is a very unique and attractive image. Kiefer was a functionalist; he designed the original Hudson which was an attractive and functional performer which other gussied up. The smoke lifters on Class S1b had a distinctive taper on the back end of them which was misconstrued as Kiefer’s own attempt at streamlining. It wasn’t. Studies had proved that this angle reduced the vortex which formed on the straight vertical lifters of the Mohawk. Still, as one looks at this model, it does look pretty racy.

Kiefer also put in all the boiler he could fit through the tunnels and other restrictions of the right-of-way. As a result, the domes are vestigial, at best, and the stack is only 7 inches tall. He also held down the exterior plumbing to a minimum. Broadway has celebrated this fact by taking what’s there and applying it separately. So when I first pulled it from the box, I photographed it and then compared what I saw to plans and photos. To see a large number of photos of not only the Niagaras but also the Mohawk and Hudson, visit the Fallen Flags web site.

My feeling is that this is a very good representation of the Niagara. All versions of the S1b Class appeared to have been delivered to NYC without air horns and wearing a single, large headlight. At some point beginning in 1946 and proceeding from there, air horns began to appear. About a year afterward, dual side-by-side Pyle National headlamps replaced the larger single type. Since this model wears an air horn but has a single, large headlight, that would place it between late 1946 and late 1949.

The model arrived in BLI’s celebrated packaging, a good way to get a model from China to your house without damage. I inspected it carefully and found everything to be in good condition. This is a chunky guy, so I put the locomotive alone on the scales and got a reading of 25.4 ounces. While one insert talks about how to install the traction tire driving axle, another one announces that this is such a good pulling loco, they felt it didn’t need the traction tires. Okay, I’d get to the By-The-Numbers testing after a bit, but first, I gave it a shot at the 40 car “heavy” train. It’s made of forty footers, all with metal wheels, Kadee couplers, NMRA weighting, but it’s still a handful for any locomotive. BLI’s A-class relinquished the point to the Niagara. Number 6001 hooked up and walked away with the train, so I’m agreed; they don’t need traction tires.

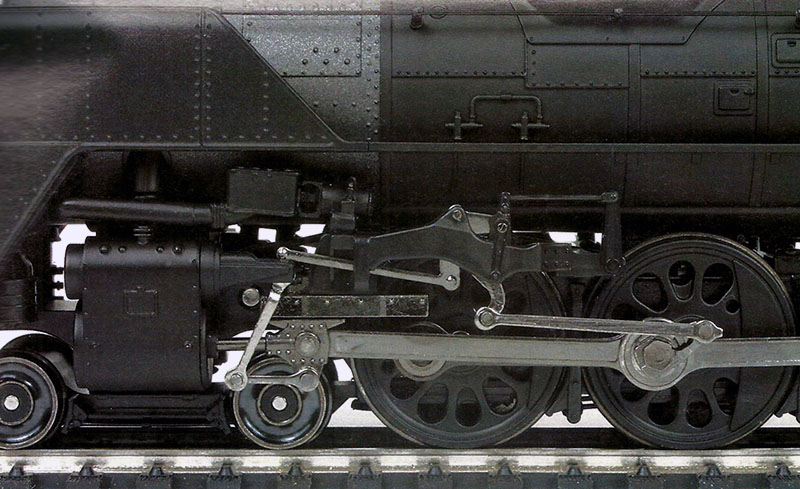

The blackened drivers look very nice, and the running and valve gear is excellently executed. This model of Baker valve gear looks just wonderful in action and is a joy to watch. The backward and downward taper of the smoke deflectors is a spotting sign for the S1b class.

As I prepped it for photos and then its first run, I hooked up the tender. This is a snap-lock drawbar, which I like, and the plug runs from the locomotive to a socket on the tender which is just the opposite of earlier BLI locomotives. You’ll have to lay the two sections on their sides, make the drawbar connection, and then carefully plug in the connector. The snap-lock drawbar allows you to pick up the loco and tender and not have them come apart while you rail the whole rig.

A word about the tender is in order. First, not only is this a pedestal (or centipede or bed) type, it was designed to take on water at an astonishing 80 mph, so fast that other track pan tenders had their sides blown out at this speed. The secret to this mechanical marvel was the venting deflector at the rear of the coalbunker. That is the most obvious indicator of the track pan scoop; the hardware underneath isn’t modeled and wouldn’t show much anyway. The spray deflector is there, however. Like the locomotive, the tender enjoys a die-cast frame which adds weight way down low, keeping the center of gravity closer to the rails. The result is a tender which follows well and can handle a lot of drawbar weight. The large overhang of the tender was designed so that the Niagara could be turned on 100-foot turntables.

This is a large locomotive, some 16 inches in length. The prototype tender was 52 feet long while the locomotive stretched 63 feet 5-1/4 inches for a total of 115 feet 5-1/4 inches. The extra length of the model is all in the front coupler which must stick out in order for the magnetic trip pin to clear the pilot. Laid atop the drawings in Steam Locomotives (Westcott; Kalmbach 1960), almost everything lined up just perfectly. I say “almost” because there were a couple of irregularities, most of the result of a model operating issues. Instead of 79-inch drivers, the model drivers come to 77.7 inches. Driver axle spacing should be 82 inches but is a bit wider at 85.5. None of this is at all noticeable except with a dial caliper. Easer to spot is that the ladder up to the cab has the bottom rung reversed. It should be angled forward but angles back instead. Big deal. Westcott contains no photos which show a Niagara with an air horn, and the drawing doesn’t have one; his work is drawn from the builder’s plans.

Nose on, she has a different face than any other Northern-type. The box cover of the Worthington SA feedwater heater sticks up just 7 inches, the same as the stack which hides behind it.

Paint and decoration is right up with the best of BLI’s past efforts. This is a Kiefer-mobile, plain black with white lettering, so the challenge is to get it smooth and sharp; BLI nailed it. The blackened drivers look very nice, and the running and valve gear is excellently executed. The test of Baker valve gear is when the eccentric rod seems to be floating in mid-air, doing its dance without regard to the machinery in the background. Since the model does that, it is a joy to watch. The cab interior is fully detailed, and light comes from the vents in the firebox door.

Sound

Being a non-articulated steam locomotive, we get a simple chuff which is pretty well synchronized. This is a QARC-equipped decoder from QSI, so it responds when running to a press of [F10] by stating in a masculine voice the running speed in scale miles per hour. This whistle is the same as BLI’s Hudson which has remained one of my favorite whistle tones. As noted above, this model wears an air horn, but I haven’t been able to find any keypress which gives us an air horn call. Unlike SP’s Daylight which also had a horn and used it extensively at grade crossings, my understanding is that the Central installed these horns for use in the yard but rarely on the main line.

Operation

Thanks to the plethora of pickups from the tender wheels, this a very dirty-track-tolerant locomotive. It ran very well on curves down to 21-inch radius, and it sort worked in 18-inch curves but it was binding some. Let’s just say that anything less than 22 inches isn’t for this locomotive. For a large wheelbase locomotive with a zillion wheels, it is remarkably tolerant of track oddities, handling #4 and #6 switches, uneven track, and turntable transition with aplomb.

As I expected, it worked just find under d.c. and DCC. People still ask me if the process of going from one type of current to the other requires flipping some sort of switch, and if so, where is it? From the original Hudson to the brand new Niagara and every QSI-equipped BLI loco in between has made the transition automatically. You don’t have to do anything but power it up.

In initial testing, the low end under analog DC was 1.5 mph while the DCC at speed step 1 came in at 3.5 mph. This was just a bit squirrely on and off the turntable, so I took the Niagara to the program track where I could read CV2. It stood at 32 so I stepped it down to 25. This didn’t start until we got to around 11 or 12 on 128-step speed table. I eventually worked it up to 30 and got a scale mile per hour reading 2.8 which is more like it.

With a top speed in the 90s, this is pretty consistent with the prototype It ran around 93 smph around 24-inch radius curves and across #6 switches, keeping her feet under her. This kind of thoroughbred performance is in keeping with the prototype, though I don’t suppose I’ll run her that fast very often.

Summary

The Niagara and the Pittsburgh & Lake Erie Berkshire were Paul W. Kiefer’s last hurrah and the final big steam puller for the New York Central System. They shared a smoke box face and a destiny; both faced incoming diesels. To the credit of the Niagara’s they could do what a trio of E7s could do running between New York and Chicago, but the diesels did it cheaper and with less servicing, no track pan action, and greater availability. After a stint pulling express freight, the last of the Niagaras was retired in 1956, barely making 10 years of existence, and none were preserved. As a result, this model is a fitting tribute to a wonderful locomotive which should have been built 10 years sooner. Broadway Limited brings not only the looks, but the sound and action any HO layout bold enough to have such a fine model.

This review appeared in the May 2005 issue of Model Railroad News

This review appeared in the May 2005 issue of Model Railroad News